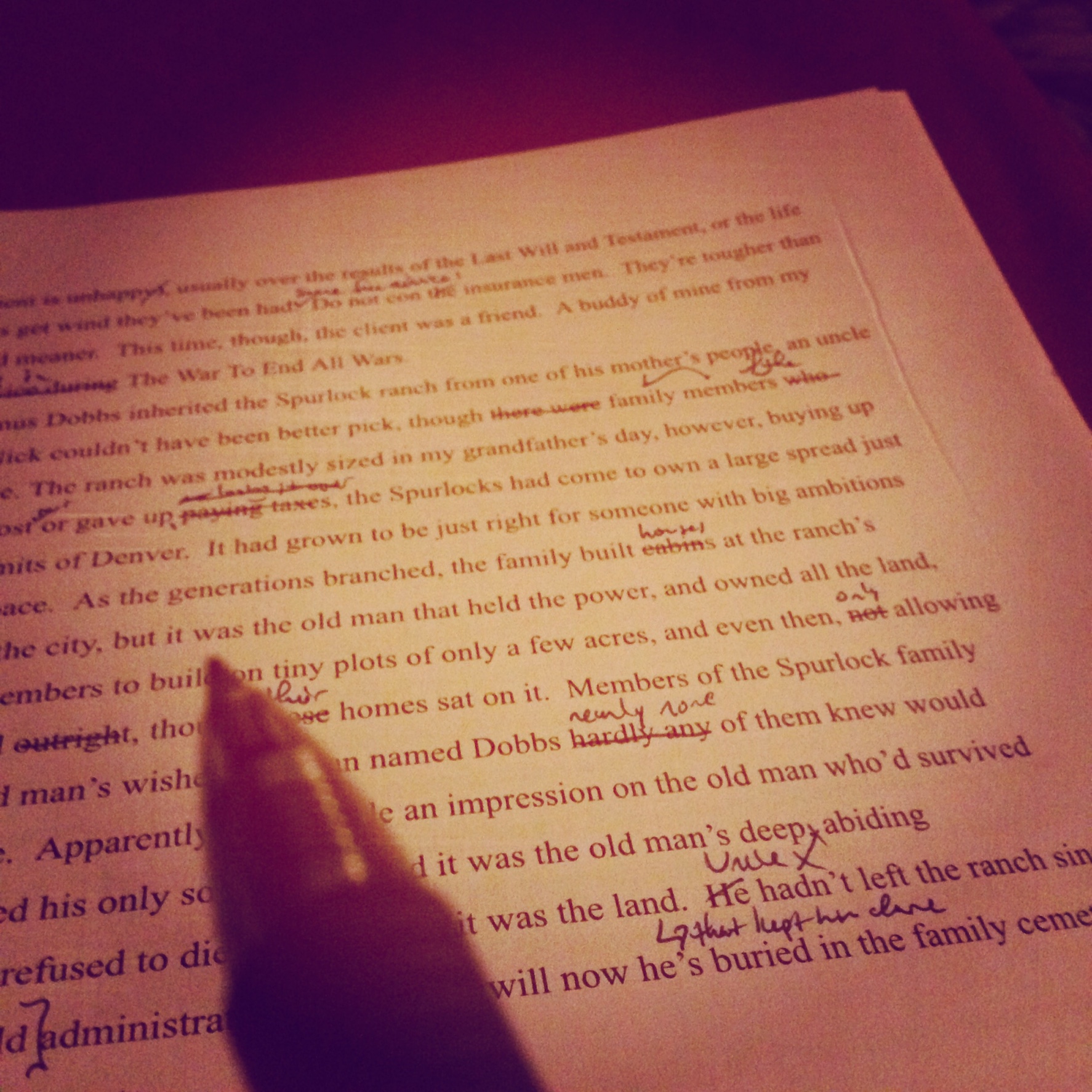

Fun times, editing, editing, editing. This one is coming together…

Comics, History, Books, Museums and more

Fun times, editing, editing, editing. This one is coming together…

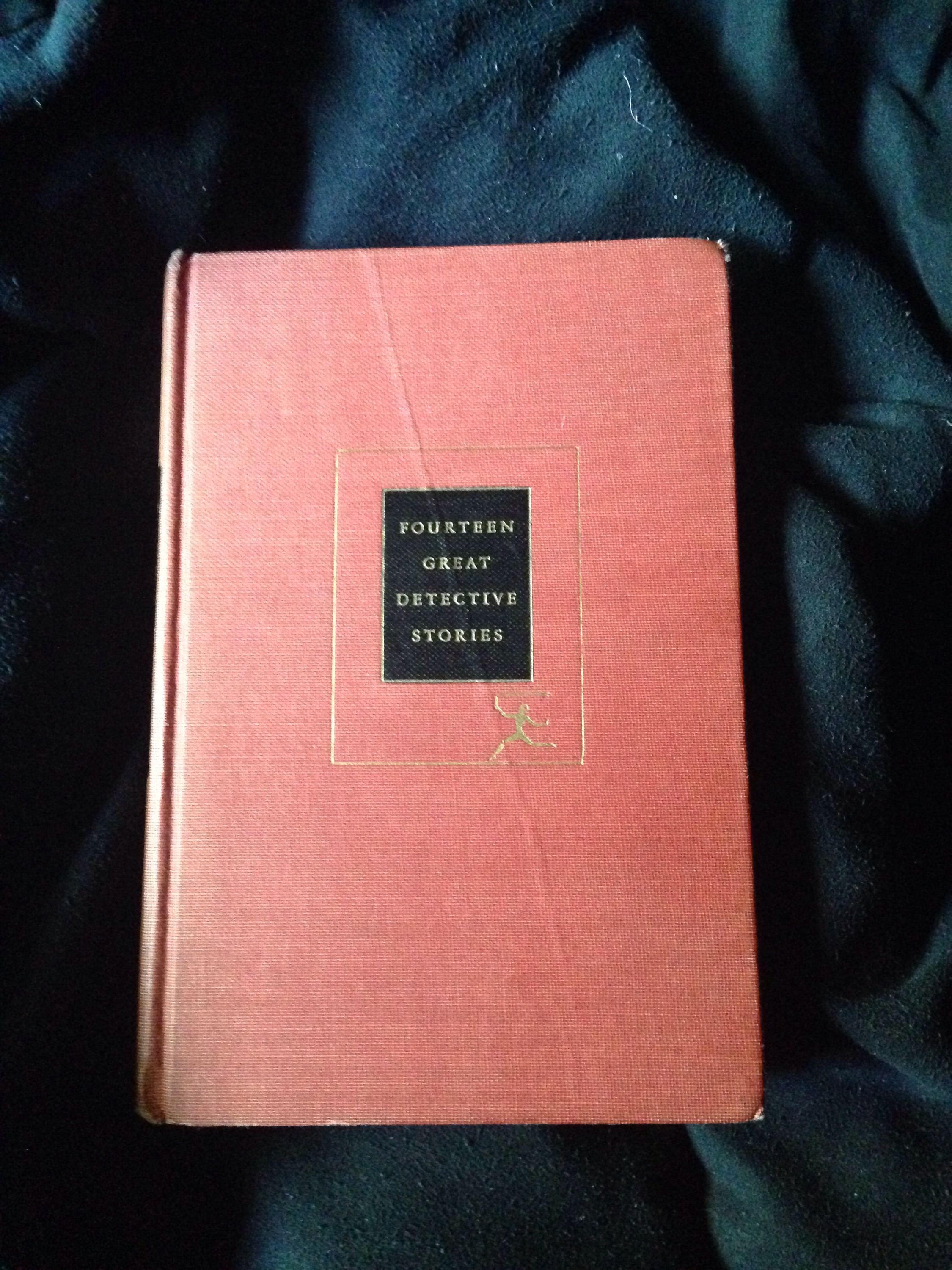

I dipped into this wonderful old anthology over the past couple of weeks. I once actively collected the Modern Library series, and this book was on those shelves, though it’s in far from collectible condition. It does have a fun old gift inscription and a big old crease through the front board, which somehow makes the book look more friendly.

Earlier I read an essay about how the story The Case of Oscar Brodski, one of the Dr. Thorndyke mysteries by R. Austin Freeman was revolutionary for being the first We See Who Commits the Crime, Will They Be Caught style of stories. In old essays about crime fiction, this is often called an Inverted Detective Story. I had nev er read Dr. Thorndyke and was not familiar at all with The Case of Oscar Brodski. Then, VOILA, springing forth from my own shelves, there it was. I think Freeman’s story holds up and was pretty good, even to this modern reader.

er read Dr. Thorndyke and was not familiar at all with The Case of Oscar Brodski. Then, VOILA, springing forth from my own shelves, there it was. I think Freeman’s story holds up and was pretty good, even to this modern reader.

However, also in this book, the real treat was Cornell Woolrich’s short story The Dancing Detective. Wow! For suspense, menace, and just a straight-up creepy story, what a knockout! The narrator’s voice was so enjoyable, with just the right amount of dark humor. The contemporary slang, also very well done and hilarious. This short story exceeds a lot of stuff coming out today, but then again, Cornell Woolrich is still considered a master of the genre.

The stories included in this edition (earlier editions had slightly different contents):

Bailey, H.C. The Yellow Slugs

Bentley, E.C. The Little Mystery

Chesterton, G.K. The Blue Cross

Christie, Agatha The Third-Floor Flat

Dickson, Carter The House of Goblin Wood

Doyle, A. ConanThe Red-Headed League

Freeman, R. Austin The Case of Oscar Brodski

Futrelle, Jacques The Problem Of Cell 13

Poe, Edgar Allan The Purloined Letter

Post, Melville Davisson The Age of Miracles

Queen, Ellery The Adventure of the African Traveler

Sayers, Dorothy L. The Bone of Contention

Stout, Rex Instead of Evidence

Woolrich, Cornell The Dancing Detective

About the Author: Benjamin L. Clark writes and works as a museum curator.

I can get swept along when writing, especially when writing dialogue. I’ve heard this state of writing is called “flow,” which makes sense. Cruising along in my current story, set sometime around 1935, and out of the mouth of one of my characters comes the word “Bingo.” I’ve never used the word outside the game with the balls and whirly wheels myself, but this fictional gent decided to say it in my story. It jolted me out of the writing, and I thought: Did anyone even use the word Bingo in the 1930s? It’s just one of the things I worry about.

In my story, I mean “Bingo” in the sense of “you got it,” not “I have aligned 5 arbitrary letter-number combinations; give me a prize.” Etymological dictionaries on my shelf say maybe Bingo goes back to 1815, the other says maybe only 1936 without much explanation. Not very helpful. I want my stories to capture language as it was used, to sound natural but be historically … well, probable, if not absolutely, strictly correct.

Etymological dictionaries say it was used in 1815, so yes, it would be fine in a story set in the 1930s, but it isn’t good enough. In historical research, we sometimes get to the point of proving if something was at all possible and ignore if it was probable. It’s setting a too low bar for historical accuracy.

This is where Google Books’ Ngram Viewer can be helpful. It uses the collective bajillion-zillion words scanned by Google Books and charts them by year published. You can use it to chart a word or phrase’s popularity in all of GoogleBooks 450 million scanned published works. It’s not definitive and may not perfectly reflect normal conversation, but it is certainly helpful to see how frequently the word was used in print. I does not include newspapers, which would be *very* useful if it would.

It turns out 1930-something isn’t a great time for the word Bingo. It was around and was used earlier, according to this chart, but has been climbing in popularity since then. The true high-water mark came in 1976, apparently. I have no idea why that would be, but that’s for someone else to chase. I have a story to get back to.

Like this post? Here’s more about historical research:

How to know Things are Bound to get Worse

How to Research History like a Novelist

About the Author: Benjamin L. Clark writes and works as a museum curator.